Adhesive elastic contact

New understandings of the role of roughness in adhesive elastic contact

Topics:

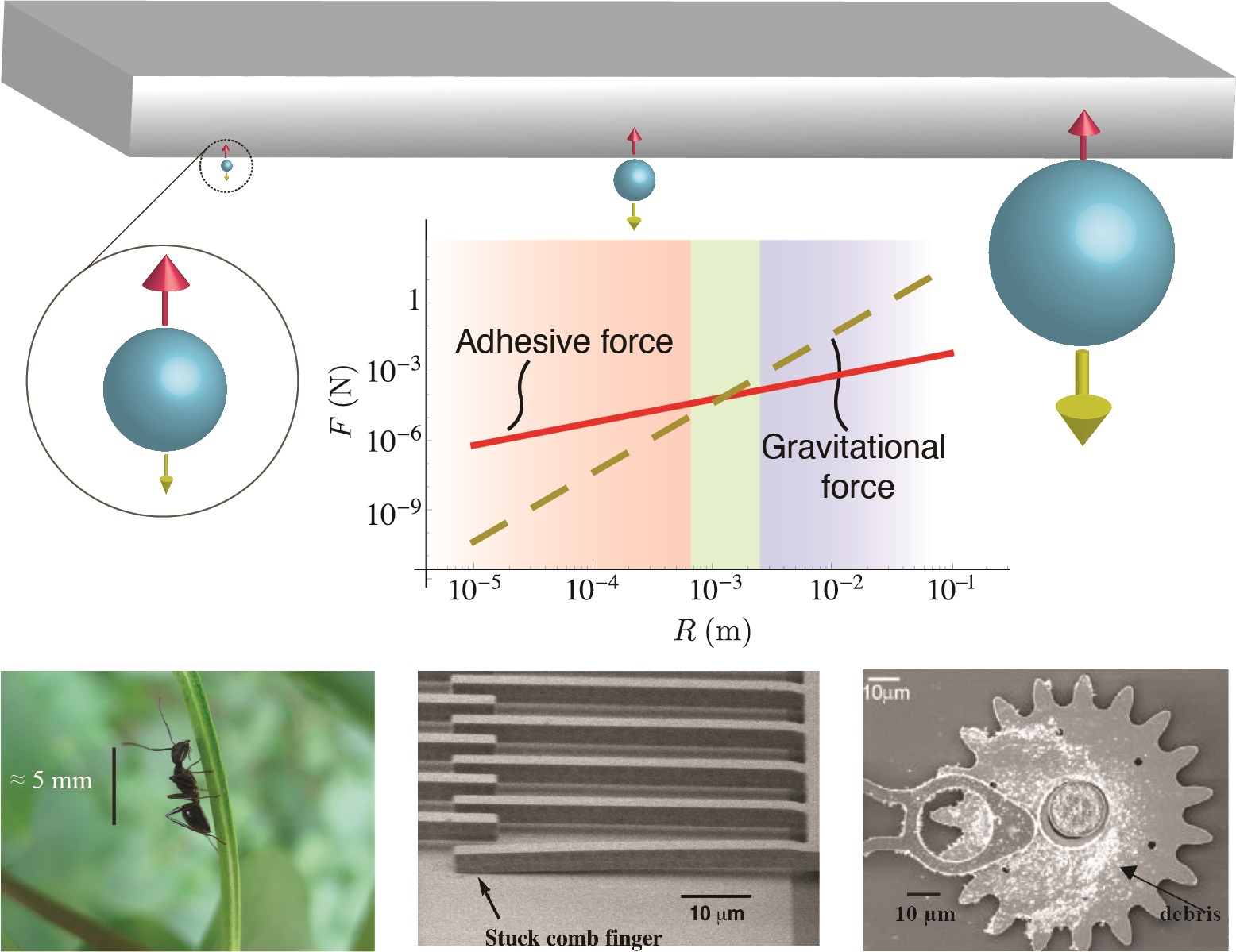

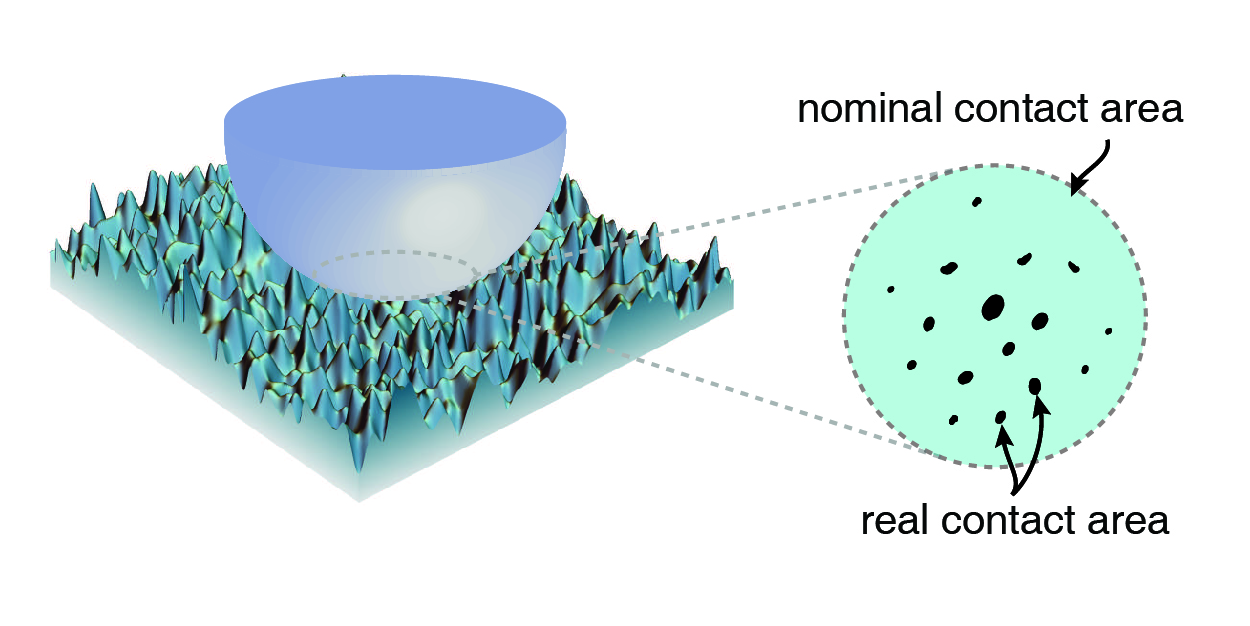

Dry adhesion plays an important role in many fields, including biology, engineering, and physics. Many insects, spiders, and reptiles, for example, possess fibrillar structures on their foot pads that, through adhesion, allow these animals to adeptly scale vertical surfaces. In microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) engineering, adhesion-induced device failure is a pervasive problem that limits its continued development. In MEMS devices, such as comb drive accelerometers, slender, micrometer-sized structures are aligned in parallel rows in close proximity to one another. During the device’s fabrication stage or later in its operation, these structures can unintentionally come into contact with each other or the substrate and remain permanently adhered, leading to device failure. Adhesion also plays a role in the physical properties that underlie friction and wear at the sub-micrometer scale. Contact between hard solids, such as metals and ceramics, primarily takes place at the surface’s asperities. Adhesion firmly welds the asperities, and thus the two solids. In order to move or slide the solids over one another, significant frictional force must be generated in order to break the asperities apart or rupture the asperities from their respective solids, contributing to wear.

Topic A: Depth-dependent-hysteresis in adhesive elastic contact

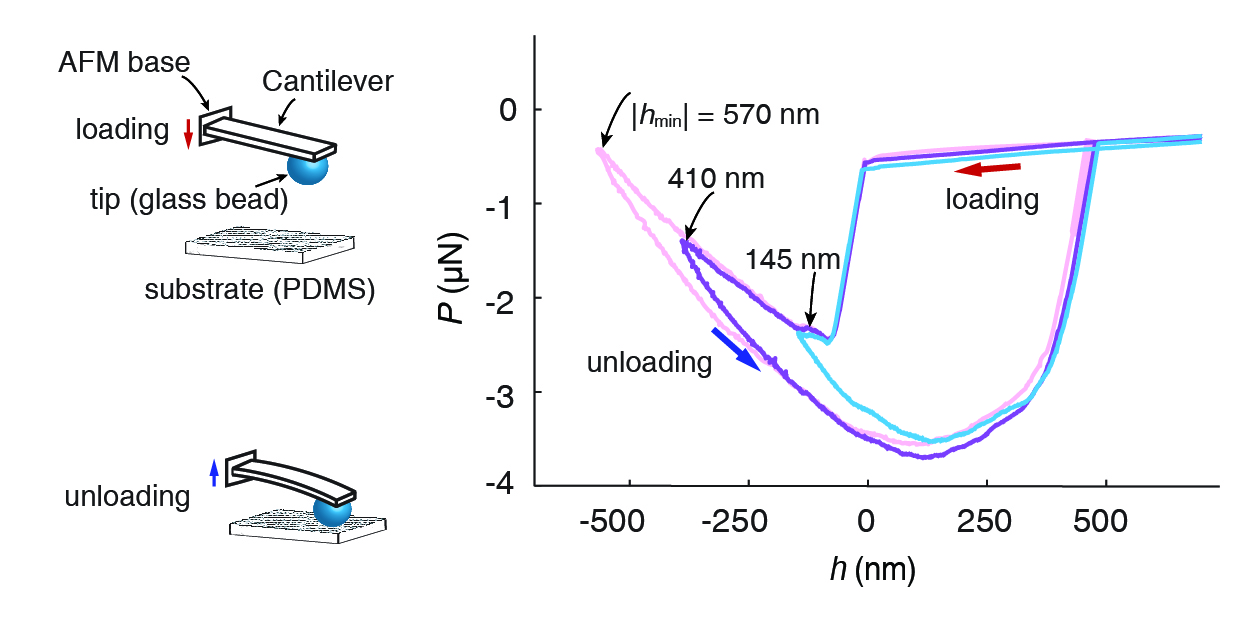

A clear understanding of adhesive contact mechanics is critical for spatially mapping out a material’s mechanical properties using, for example, nanoindentation- and contact mode atomic force microscopy (AFM)-based techniques. Typically, material properties are measured by fitting contact force vs. indentation depth (P–h) measurements to a contact mechanics theory. Some of the most popular theories for modeling adhesive elastic contact include the Johnson–Kendall–Roberts (JKR), the Derjaguin–Muller–Toporov (DMT), and the Maugis–Dugdale (MD) theories. These classical contact theories predict that when the solids are in physical contact, the force is uniquely determined by the indentation depth and is independent of the history of the contact process. However, in many experiments it is found that the contact forces depend on the contact process history. A typical contact experiment consists of one or more contact cycles, each of which consisting of a loading and an unloading phase. In those phases the solids are, respectively, being moved towards and away from each other. It is found that, at a given indentation depth, the contact force differs depending on whether the experiment is in a loading or an unloading phase. For example, Kesari et al. reported AFM-based contact experiments between a glass bead and a poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) substrate, which shows that the contact forces differ between the loading and unloading phases. The force during the unloading phase was also observed to depend on the maximum indentation depth. Kesari et al. termed this phenomenon depth-dependent-hysteresis (DDH).

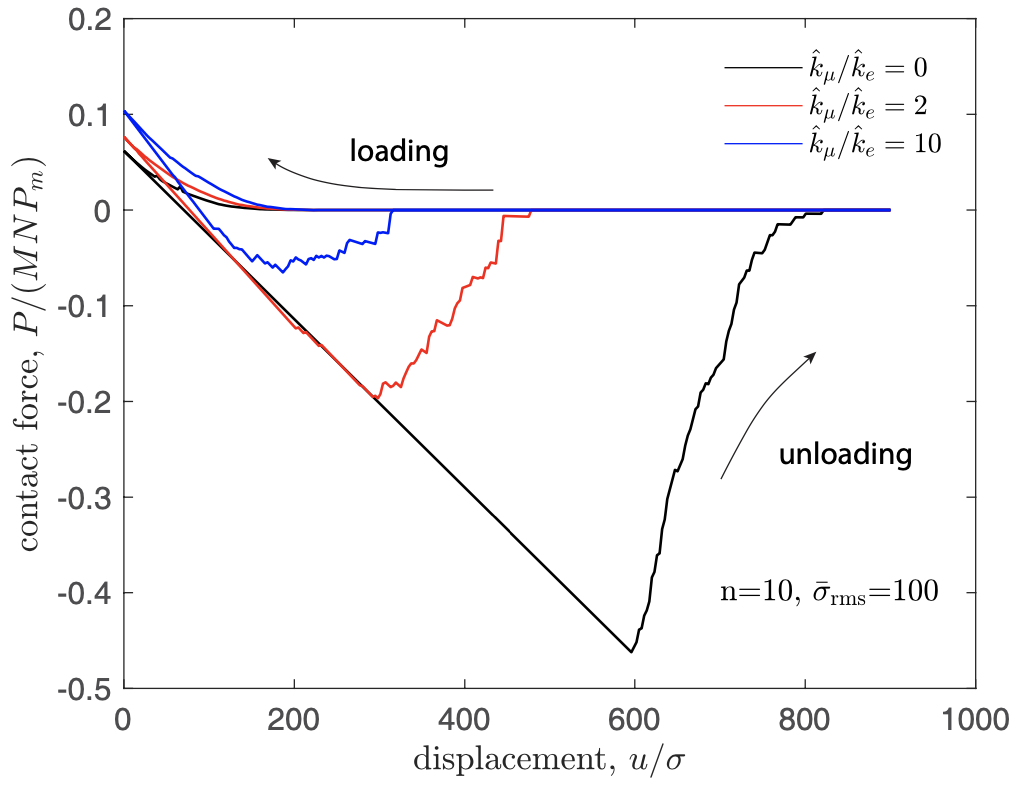

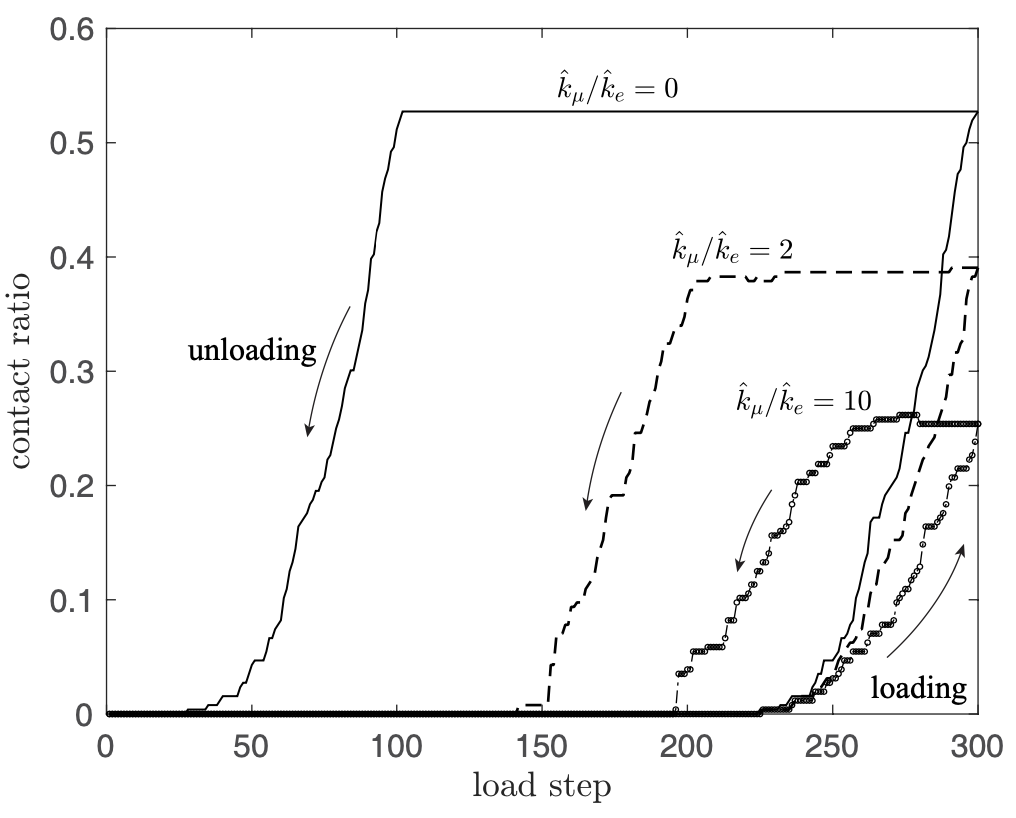

We carried out molecular statics simulations that capture DDH. We found that DDH is due to a series of surface mechanical instabilities. Surface features, such as depressions or protrusions, can temporarily arrest the growth or recession of the contact area. With a sufficiently large change of indentation depth, the contact area grows or recedes abruptly by a finite amount and dissipates energy.

Furthermore, we presented a new mechanics model for explaining DDH that applies in the regime of large surface roughness based on the Maugis–Dugdale theory of adhesive elastic contacts and Nayak's theory of rough surfaces. The model is based on the occurrence of adhesion and roughness related small-scale instabilities as revealed by our molecular statics simulations. The model captures the trend of decreasing energy loss with increasing roughness. It also captures the experimentally observed dependencies of energy loss on the maximum indentation depth, and material and surface properties. Read news coverage.

Topic B: Adhesion enhancement by surface roughness

We proposed an effective, nonlinear body force based finite element method to numerically investigate the effect of surface roughness on adhesion in adhesive elastic contacts. The most notable feature of this study is that it reveals the mechanisms of the depth dependent hysteresis (DDH) and the adhesion enhancement by surface roughness observed in many adhesive contact experiments. Our simulation captures DDH and reveal that DDH originates from small-scale contact instabilities at the surface asperity level. Both adhesive force and hysteretic energy loss first increase then decrease with increasing surface roughness. The adhesion enhancement effect of rough surfaces is resulted from the increased contact area in the small roughness regime. Our simulation gives other interesting insights into the mechanics of adhesive contact between rough surfaces. It shows that the change in the trend of roughness effect on adhesion correlates with the transition of contact region from being simply connected to multiply connected. The interactions between surface asperities become weaker and the contact becomes asperity type as roughness increases. These new findings cannot be captured by theoretical contact models.

Topic C: The principle of contact splitting

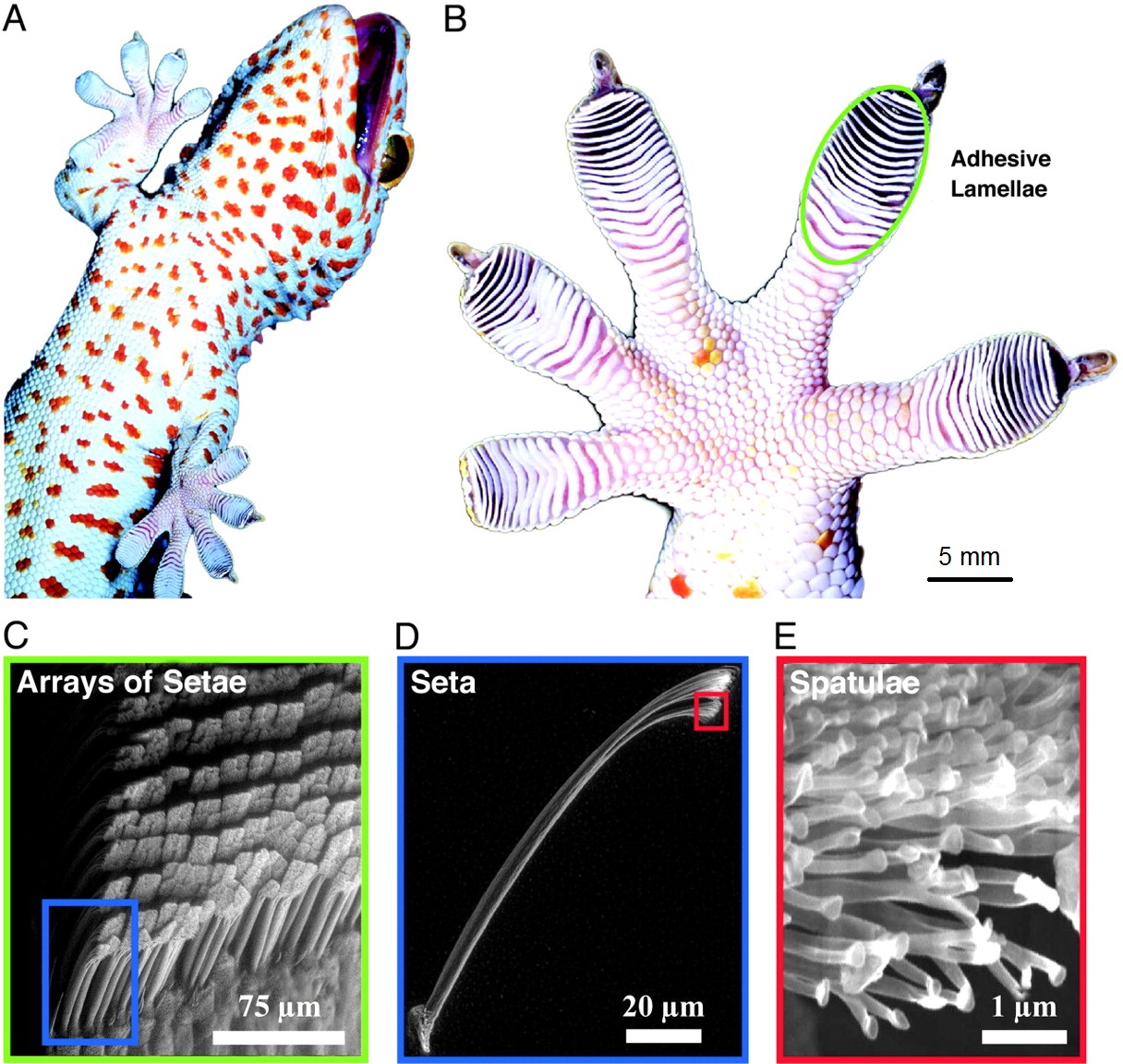

Many animals such insects, spiders, and lizards have developed an alternate strategy—fibrillar structures on their attachment pads—to achieve remarkable adhesion and easy release for locomotion on natural rough surfaces. The biological fibrillar structures allow individual fibril to deform more easily to conform with the rough surface, which can give rise to larger contact area and strong adhesion for relative stiff biological materials, such as β-keratin protein in gecko’s attachment pad that has an elastic Young’s modulus of ≈2 GPa.

Analytical models based on adhesive elastic contact mechanics have been proposed to understand adhesion properties of fibrillar structures. Among those models, the critical mechanism is based on the principle of contact splitting—by which splitting contact into finer sub-contacts. We considered gecko’s adhesive pad as a paradigm and proposed a multiple spring model to investigate the adhesion properties of fibrillar structures on rough surface. The results demonstrate that the contact splitting can significantly enhance adhesion of fibrillar structures on rough surface.